by Anne Key | Apr 23, 2018 | Mesoamerican Goddesses, Tour

One of the most fascinating deities of pre-Columbian Mexico is Coyolxauhqui. At first glance, a deity named “She Who is Adorned with Bells” might seem to be a dancer, until we read that warriors wrapped strings of bells around their calves before going to battle. Then we see Coyolxauhqui (Nahuatl: coyolli = small metal bells) as a warrior, suiting up for battle.

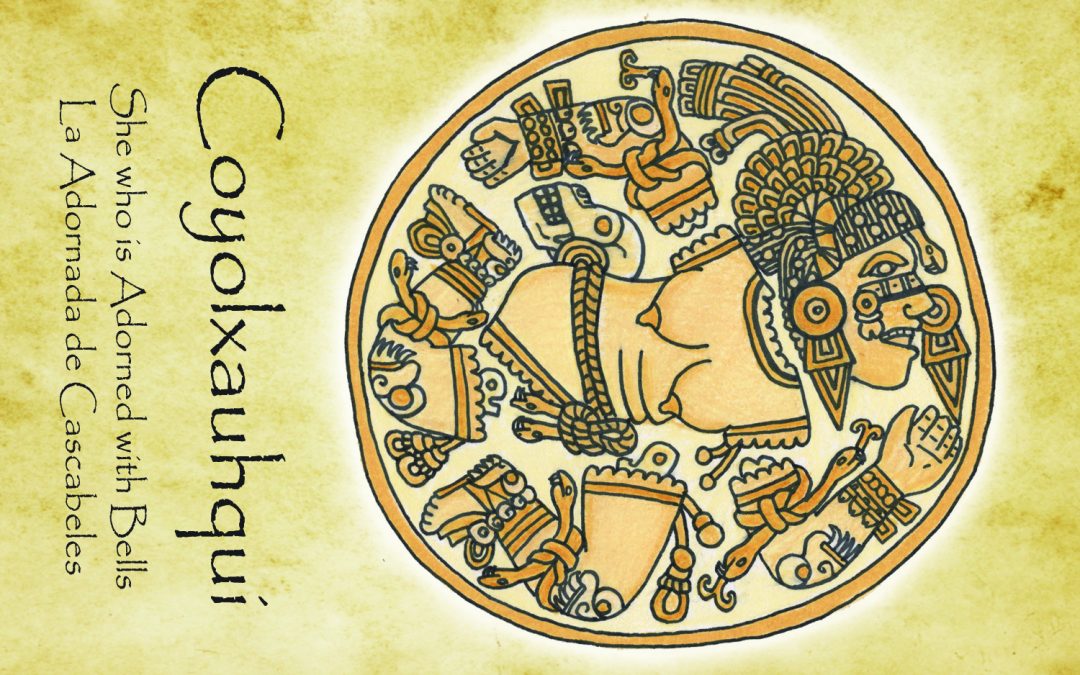

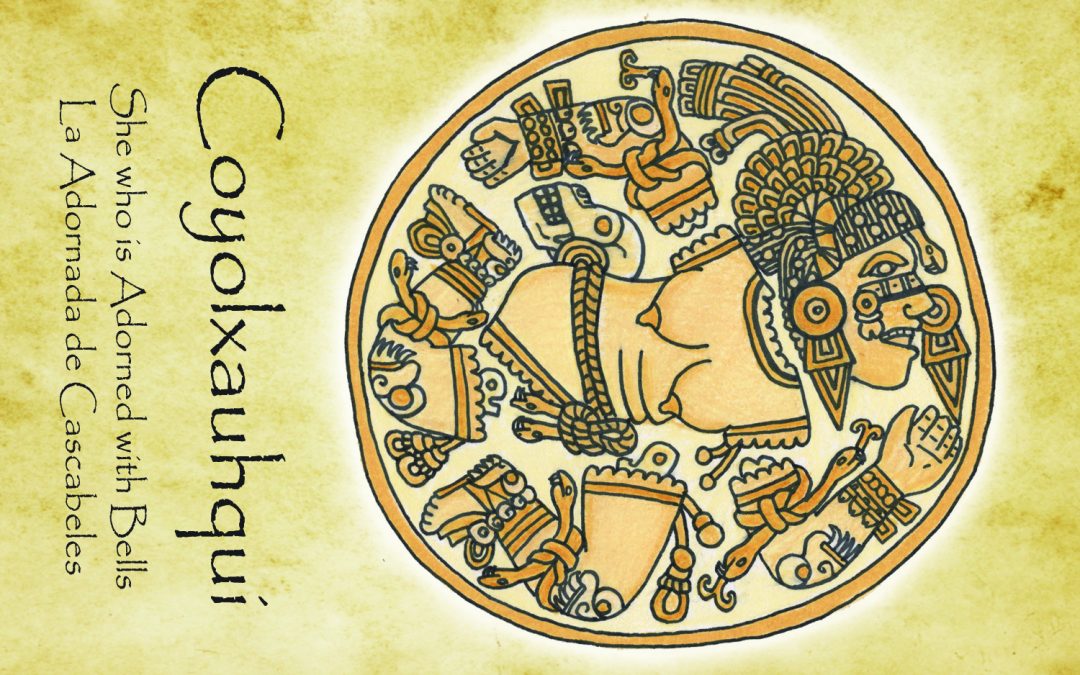

The image of Coyolxauhqui is beautifully rendered in the massive stone relief that was found at the Great Temple (Templo Mayor). Construction of this temple began in 1325 CE, and it was the main temple of worship for the Aztecs in their capital of Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City). The Templo Mayor was dedicated to two deities, Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli. Tlaloc (Lord of rain) was most likely a local deity before the Aztecs arrived. Huitzilopochtli (Left Hummingbird) was the warrior deity of the Mexica, accompanying them on their sojourn from northern Mexico to Tenochtitlan, which resides in the altiplano, or high plains, of central Mexico. The Templo Mayor may have been a symbolic representation of the Hill of Coatepec, recounting the story of Huitzilopochtli’s birth and Coyolxauqui’s demise.

The Templo Mayor was a large structure at 328’ x 262’ at its base. Rebuilt six times, its excavated ruins are on the northeast edge of the zócalo, or city center, of Mexico City. The Spanish used the stones from the temple to build what is now known as the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral, a massive structure situated atop the Templo Mayor. But careful excavation, and some lucky breaks, have brought both the temple and many of its monolithic sculptures to light.

In February of 1978, while workman for an electrical company were digging, they discovered the giant disk of Coyolxauhqui. The stone disk is 10.7 feet in diameter, almost a foot thick, and weighs over 9 tons. Her discovery set off a wave of archaeological work on the Templo Mayor.

Coyolxauhqui is the second largest sculpture found in the temple. This exquisitely carved disk encircles her. She is dressed in full battle gear with balls of eagle feathers in her hair, attesting to her bravery and courage. A large ceremonial headdress sits atop her head, and her ears are adorned with pendulous earrings. A “warrior’s belt knotted from a double headed snake” winds around her waist (Kroger 189). Her belly is puckered, showing that she has given birth. She is a mother and a warrior.

eagle feathers in her hair, attesting to her bravery and courage. A large ceremonial headdress sits atop her head, and her ears are adorned with pendulous earrings. A “warrior’s belt knotted from a double headed snake” winds around her waist (Kroger 189). Her belly is puckered, showing that she has given birth. She is a mother and a warrior.

Looking closely at her stone relief, we see a curious space between her limbs and torso, between her neck and head. Her arms and legs, attired with the pads and bindings of a warrior, are dismembered. A bit of bone sticks out from each thigh and upper arm. Her head is also separated from her body, almost unnoticeable. Even dismembered, she is resplendent with dynamic warrior energy, the circular stone emphasizing her strength, evoking the idea that she is hurtling forward.

When I stand in front of her, in the museum at the Templo Mayor, the first emotion I feel is strength and bravery. Her dismemberment does nothing to diminish her power, for she continues on in spite of all the odds. She is unstoppable.

When I meet her in visions, Coyolxauhqui barely has time for me. She is surrounded by training warriors, shouting directions and giving orders. She looks me straight in the eye and says “don’t you dare make me fit into whatever story you want to tell.” She requires me to tell her story, unapologetically.

She exudes the power and potency of warrior women, both mythic and contemporary: Boudica, Athena, Joan of Arc, Hyppolita, Atalanta, Wonder Woman, Xena, and Trinity.

Unfortunately, the myth of Coyolxauhqui is not in her own words. The story we have of her is one that reinforces a patriarchal worldview, showing favor on women who are kind, all-loving “mothers” and killing upstart rebels. This is a pattern we know well.

When I approach the story of Coyolxauhqui, I work to find the “back story,” to fill out the entire narrative sequence. We will start with the myth as it was written by the Spanish cleric Bernardino Sahagún in The Florentine Codex. This mytho-historic account begins, and ends, with Huitzilopochtli, for this story, written by the victors, can be read as a myth explaining how the Mexica inserted their deity into the local lore, and how he was victorious.

This mytho-historical saga takes place during the migration of peoples from Aztlán, the ancestral home of the peoples that came to live in the place that is now Mexico City. Aztlán was possibly located in northern Mexico or the Southwest of the United States, and the migratory groups consisted of many tribes, including the Mexica. Along the way, the migrating group encountered many villages cultures, and one of these was the peoples of Coatepec.

The myth of the birth of Huitzilopochtli, which contains the only story of Coyolxauhqui, says very little of her strength, courage, and power. Instead, it paints her as the instigator of her mother’s assassination. Huitzilopochtli was a traditional Mexica deity, and he is the embodiment of male strength and warrior energy. He was one of the most celebrated deities of what would become the Aztec civilization.

The myth recalls a time during the migration from Aztlán when the people settled briefly at Coatepec, the “hill of the snake.” The deities living at Coatepec were Coyolxauhqui, her mother Coatlicue (She of the Serpent Skirt) and her 400 brothers (the Centzon Huitznahua). The myth opens with Coatlicue sweeping the temple.[1] She finds a bundle of precious feathers, picks them up, and keeps them underneath her clothes. These feathers make her pregnant.

When her sons, the 400 brothers, and her daughter, Coyolxauhqui, discover her pregnancy, they are enraged, saying that the pregnancy “insults us, dishonors us” (Markham 382). They ask her who fathered the child, but she does not answer. Coyolxauhqui leads the brothers in a plan to kill their mother, Coatlicue. While this seems a strong response, later we find out that the child in Coatlicue’s womb is Huitzilopochtli, the warrior deity of the migrant peoples, the Mexica.[2]

Meanwhile, Huitzilopochtli, from the womb of his mother, Coatlicue, tells her: “Do not be afraid, I know what I must do” (Markham 382).

In the myth, Coyolxauqui “incited them, she inflamed the anger of her brothers, so that they should kill their mother. And the four hundred gods made ready, they attired themselves as for war” (Markham 383), including tying bells (oyohualli) on the calves of their legs.

Let’s take a moment and unpack what has happened so far. We have a group of migratory Mexica bringing a new deity to an existing culture. This becomes the story of how Coyolxauhqui defended her land and culture from the Mexica, presenting her as the military leader, the defender. And, it paves the way for Huitzilopochtli to insert himself (literally!) into the myth of Coatepec, converting the primordial mother of the Coatepec culture into his birth mother and shaming their greatest warrior, Coyolxauhqui.

Returning to the myth, Coyolxauhqui is marshalling the troops for war. One of the 400 brothers, Cuahuitlicac, turns against the rest of his family and informs Huitzilopochtli (still in Coatlicue’s womb) of the plan of attack. At the moment Coyolxauhqui and the 400 brothers approach their mother, Huitzilopochtli is born in full battle gear. He takes the Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, and strikes Coyolxauhqui, cutting off her head. Her body rolls down the hill of Coatepec, arms and legs separating as she falls.[3]

Huitzilopochtli drove the 400 brothers off Coatepec, slaughtering them. Some escaped to the south, but those killed by Huitzilopochtli were stripped of their “gear, their ornaments,” and Huitzilopochtli “took possession of them…introduced them into his destiny…made them his own insignia” (Markham 386).

This myth can be seen as a cautionary tale of women’s diminished power in the newly formed Aztec society. M. J. Rodríguez Shadow, in her book La Mujer Azteca, writes that there is ample evidence of matrilineal and matrifocal societies in Mesoamerica before the 14th century CE (1997, p. 68). However:

During the epoch of the Aztecs the religion glorified masculine values, erasing whatever vestige of that phase [matrifocal] existed, quickly and efficiently, replacing them with male gods and men, destroying allegorically the feminine figures (like Coyolxauhqui) that could have occupied positions of power or discrediting those [female figures] that they wanted to retain (like Malinalxóchitl).[4] (p. 69)

Moreover, in this myth Huitzilopochtli appropriates Coyolxauhqui’s warrior aspect. Art historian Janet Berlo puts this myth in context:

But one of the central myths of the Aztec empire is the struggle between the newly born male warrior god and the warrior goddess who preceded him. I believe this myth structurally embodies the ideological struggle between the Great Goddess of the Central Mexican past and the new Aztec order in which the significant ties of mythic kinship are redrawn to emphasize the male lines of Huitzilopochtli…. In this fraternal kinship network, the northern invaders and their ancestral god Huitzilopochtli are firmly linked with the Central Mexican past… (Berlo 1993)

The giant stone sculpture of Coyolxauhqui was found at the foot of the stairs of the Templo Mayor, on the side dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. It may have been hurtled down the stairs, just as she was thrown from Coatepec. While it may have been put there as a symbol of defeat, the sheer size of it is a reminder of the threat she presented.

The giant stone sculpture of Coyolxauhqui was found at the foot of the stairs of the Templo Mayor, on the side dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. It may have been hurtled down the stairs, just as she was thrown from Coatepec. While it may have been put there as a symbol of defeat, the sheer size of it is a reminder of the threat she presented.

On a personal note, living in these times, I feel like the dismembered Coyolxauhqui. I feel as if all I have worked for to make life better for myself, my students, my friends and neighbors in this great country is being dismembered. But, like Coyolxauhqui, I remain whole and strong. #metoo, #marchforourlives, #blacklivesmatter and so many more have grown from this fractured political environment. Coyolxauhqui is a testament to the power, strength, and resolve of those who have been defeated. In the Museum of the Templo Mayor where she resides, her spirit pervades the space, a permanent reminder of the warrior women and cultures that are in the earth and spirit of Central Mexico.

References:

Berlo, J. (1993). Icons and Ideologies at Teotihuacan: The Great Goddess Reconsidered. In J. C. Berlo (Ed.), Art, ideology, and the city of Teotihuacan (pp. 129-168). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Markman, R. H., Markman, P. T. (1992). The Flayed God: The Mesoamerican Mythological Tradition. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

Rodriguez Shadow, M. J. (1997). La mujer Azteca [The Aztec Woman]. Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México.

[1]Sweeping has a deeply ritual context for the ancient Mexicans. An entire festival, Ochpaniztli, was dedicated to sweeping the streets, private homes, and temples, preparing for harvest. Tlazohteotl, another Goddess, is shown with a broom, showing her connect to this festival.

[2]This brings up a number of different ideas. Did Coatlicue “change sides,” going against her people? Was she raped? Or did Coyolxauqui and her brothers know that if this god was allowed to birth through their mother, that it would be the end of Coatepec as they knew it?

[3]The statue of Coatlicue that once stood in the Templo Mayor replaces her arms with the Xiuhcoatl. Could it be possible that the Xiuhcoatl was a symbol of the culture at Coatepec, and that this was coopted by the migrating Mexica?

[4] En tiempos de los Aztecas la religion enaltecía los valores masculinos, borrando cualquiere vestigio de aquella fase y consolidando con eficacia y rapidez la sobresaliente posición de los dioses masculinos y los varones, destrozando alegóricamente las figuras femeninas (como Coyolxauhqui) que podia ocupar el poder o desacreditar a las que desearan compartirlo (como Malinalxóchitl).

Click here for more information on the Jade Oracle. Visit our Goddess Ink Media for videos about The Jade Oracle. For more information on Goddess Ink, visit our website and circle with us on Facebook and Instagram. Check out our newly designed store and please sign up for the Goddess Ink Newsletter for a monthly dose of inspiration. If you would like a weekday dose of daily inspiration sign up for our Daily Inspiration newsletter.

Special Introductory price for the Jade Oracle deck:

Special Introductory price for the Jade Oracle deck:

$45 until May 5th 2018 (Cinco de Mayo)! Find out more and purchase here.

Visit our Goddess Ink Media for videos about The Jade Oracle. For more information on Goddess Ink, visit our website and circle with us on Facebook and Instagram. Check out our newly designed store and please sign up for the Goddess Ink Newsletter for a monthly dose of inspiration. If you would like a weekday dose of daily inspiration sign up for our Daily Inspiration newsletter.

_______________________________________

Priestess, instructor, writer and dancer – Anne Key, Ph.D. has traveled, researched, and written about Mesoamerican culture since 1990; her dissertation investigated the pre-Hispanic divine women known as the Cihuateteo, and she is co-founder and guide for Sacred Tours of Mexico. She was Priestess of the Temple of Goddess Spirituality Dedicated to Sekhmet, located in Nevada and has edited anthologies on women’s spirituality, priestesses, and Sekhmet as well as written two memoirs, Desert Priestess: a memoir and Burlesque, Yoga, Sex and Love. An adjunct faculty in Women’s Studies, English and Religious Studies, she is co-founder of the independent press Goddess Ink. Anne resides in Albuquerque with her husband, his two cats and her snake, Asherah.

Priestess, instructor, writer and dancer – Anne Key, Ph.D. has traveled, researched, and written about Mesoamerican culture since 1990; her dissertation investigated the pre-Hispanic divine women known as the Cihuateteo, and she is co-founder and guide for Sacred Tours of Mexico. She was Priestess of the Temple of Goddess Spirituality Dedicated to Sekhmet, located in Nevada and has edited anthologies on women’s spirituality, priestesses, and Sekhmet as well as written two memoirs, Desert Priestess: a memoir and Burlesque, Yoga, Sex and Love. An adjunct faculty in Women’s Studies, English and Religious Studies, she is co-founder of the independent press Goddess Ink. Anne resides in Albuquerque with her husband, his two cats and her snake, Asherah.

Come see Coyolxauhqui and other wonders with Anne and Veronica Iglesias with Sacred Tours of Mexico!

by Anne Key | Jan 22, 2018 | Mesoamerican Goddesses, Tour

For travelers from the United States, Mexico City is a fantastic destination. It is within easy distance from anywhere in the United States, boasts world-class ruins and museums, and is a fraction of the cost of Europe. Here are 10 of our favorite things to do in Mexico City:

- Teotihuacan: Stand atop the largest pyramid in the world and then submerge yourself in the ancient murals, still brilliant and colorful after two thousand years. Sit in front of the famous Gran Diosa de Teotihuacan mural and be transported back to a society filled with life and beauty.

- Museum of Anthropology: Visit a seriously world class museum, the Museum of Anthropology, which houses the finest artifacts from across Mexico, including the colossal and awe-inspiring Coatlicue, Tour the Museum of Anthropology with your expert guides and then sit, relax, and enjoy the astonishing Danza de los Voladores de Papantla.

- Basilica de Guadalupe: Experience the most visited religious site in the West, the Basilica de Guadalupe. See the image of La Virgen on Juan Diego’s cloak and take a moment to light a candle for your loved ones. Climb the stairs to the chapel at the top of the Hill of Tepeyac, the original worship site of Tonantzin, and tour the ornate chapel.

- Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera: See how two of the most well-known names from Mexico City lived and the indelible mark their art has left on its culture. Wander through Casa Azul, Frida’s house and museum, and see her studio. Visit Anahuacalli, a museum of pre-Columbian art designed and curated by Diego Rivera. Stand in awe of Rivera’s murals in the National Palace building.

- Xochimilco: Board a brightly colored boat and join the party, meandering through over 50 miles of canals that make up Xochimilco, a World Heritage Site referred to as the “Venice of Mexico.” Surrounded by flowers and tropical plants, wait a moment for vendors to row by and grab some lunch and beer, and there are always a few boats filled with mariachis!

- Mercado Jamaica: Wander through the “Flower Market,” Mercado Jamaica. Teeming with color, sounds, and smells of everything beautiful and delicious in Mexico, this market is a treat for the eyes and palate.

- Temazcal: Experience an indigenous “sweat bath” and ceremony, lead by a local curandero/a. Leave the ritual knowing that you have left behind what you do not need.

- Museum of the Templo Mayor and the Zocalo: Stand in the center of the heart of Mexico City, the Zocalo, which has been the political and spiritual capital continually from 1325 CE to the modern day. In the museum, stand at the feet of two of the largest deity statues in the region, Tlaltecuhtli and Coyolxauhqui, and feel yourself transported to ancient times.

- The Historic District: Wander the network of pedestrian streets in the Historic District, A UNESCO World Heritage site (and location of our hotel!). This area hosts a pageant of architecture from the 16th century to Art Deco to Modern, with boutiques and cafes nestled in every corner.

- Tacos, tequila and pulque: We know, these are actually three reasons, but they all seem to go together. Mexico City is in the midst of a culinary renaissance, so get ready to try artesanal tacos using pre-Columbian ingredients, craft pulques (a fermented sacred beverage made from the maguey cactus) and the finest tequilas and mezcales.

by Anne Key | Mar 7, 2017 | Mesoamerican Goddesses

My heart is a flower, the corolla opens;

Ah! It is the mistress of midnight and She has arrived

Our Mother, the Goddess Tlazolteotl.

(Hymn to Tlazolteotl, from Baéz-Jorge 101)[1]

She is easily identified, usually with black around her mouth, sometimes with a conical hat or riding a broom, and often squatting in a birth-giving posture.

Tlazolteotl is one of the most endearing and complex goddesses of the Mesoamericans.

Her name is derived from the Nahuatl word for garbage, tlazolli, literally “old, dirty, deteriorated, worn-out thing … which was used to connote filfth, garbage, or refuse, all of which subsumed human waste products” (Klein 21). Tlazolli could also refer to profligate behavior, related to the root for quail (zolli), a bird associated with fertility and the earth “owing to its tendency to keep close to the ground and to its prolific breeding habits” (Sullivan 11). Indeed Tlazolteotl both provoked and pardoned licentiousness, explaining Her moniker “The Eater of Filth.”

The second part of Her name, teotl, signifies a deity, and in this generic form could refer to male or female. However, Tlazolteotl is almost always considered female. The early Spanish clerics compared Her to the Roman Venus because of Her connections to sexuality. Tlazoltetol not only encompasses illicit love, overindulgence, and dissolute behavior but also is the pardoner for those who engage in Her excesses.

Tlazolteotl is considered a lunar and agrarian Goddess. She is identified with the trecena [2] of the ritual calendar that begins with the day Ce Ollin, or First Movement. She is associated with the day sign of the jaguar. She was honored by the peoples of eastern coastal Mexico, the Huastecs, Mixtecs, and Olmecs, as well as the Aztecs of central Mexico. She was known by various names, including Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina and Tlazolteotl-Tlaelquani, indicative of Her many aspects.

Fertile and Generative Black

Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina originated in the rich fertile areas of the Huastec peoples in the lands bordering the Gulf of Mexico in the modern states of Hidalgo, Veracruz, San Luis Potosí and Tamaulipas. The Huastec region is a rich fertile area, especially known as a cotton growing region, with a long history of trading with Central Mexico. In a statue from post-Classic Huastec, Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina wears a conical hat indigenous to this region.

On page 39 of the Codex Borgia [3], a ring of Cihuateteo (women who died in childbirth and were deified) dance around two figures. The Cihuateteo wear the typical red and black skirts and huipils of Tlazolteotl, adorned with crescent moons. The shells on their skirts, as well as the typical Huastec crescent moon nose ornament, connect them with the lunar cycles. Though the moon was considered the purview of a male deity, the cycles, the regenerative aspect, and the motion were female.

A number of Tlazolteotl figurines were part of an offering burial in honor of the Cihuateteo. These figurines show Tlazolteotl in Her aspect as midwife. In each hand She holds the bands used in traditional postpartum binding practice.[4] Though more obvious on these figurines in person than in photo, Her mouth is painted black.

In fact, Tlazolteotl’s most distinctive feature is the black on Her mouth and chin. The Olmecs used bitumen, a black viscous material, as paint for decoration on everything from pottery to the human body. Bitumen was chewed publicly only by girls and unmarried women (McCafferty 33)[5].

Bitumen (also called tar or asphalt) is the byproduct of decomposed organic materials. Could there possibly be a more apt decoration for Tlazolteotl than a paint made of deep, black, decomposed material associated with the burgeoning sexuality of young women? The black around Her mouth is linked with Her role as an “eater of sins,” as the “eater of filth,” but here the sin and filth are transformed into symbols of the dark erotic genesis of life.

Spinning, Weaving, and Sex

In her name Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina, the Ixcuina is from the Huastec for “Goddess of Cotton” (Sullivan 12). Her headdress usually includes two spindles of unspun cotton, which connect Her to weaving and to the rich cotton-growing region of the Huastec.

In Mesoamerica, woven cotton textiles were used as a medium of exchange, and women were the principle weavers, bringing money and prestige to the household through their weaving. A spindle full of thread is also called a mazorca, the word for a full ear of corn, as they are similar in form. The strands of cotton that hang from the spindles in Her headdress mimic the tassel on the ear of corn. The life-cycle of corn parallels the cycle of spinning, from waxing to waning, and both parallel the human life cycle (Sullivan 28-29). Cotton had other connections to the female cycle, as the bark of the cotton plant was used for uterine contractions and to induce menstruation (Sullivan 19).

The act of weaving also had sexual connotations, as we see in this Nahuatl riddle: “What is it that they make pregnant, that they make big with child in the dancing place? The answer is ‘The spindles,’ and the dancing place is the bowl where the spindles are set” (Sullivan 14). Spinning and weaving were tied to women’s lives in metaphoric and concrete ways.[6]

Tlazoteotl-Ixcuina is associated with a four-part sisterhood: First Born, Younger Sister, Middle Sister, and Youngest Sister, each of which is named Tlazolteotl. This quadripartite representation may have lunar aspects, as the four phases of the moon (Baéz-Jorge 100). These sisters were the goddesses of carnality or lust, and the cleric Sahagún writes that “their names signified that all women have an aptitude for carnal acts” (36). I interpret this as an illustration of the female capacity, throughout her life, to embody the sacred cycle of generation, death, and regeneration. And certainly lust, the drive for connection and regeneration, is seated deeply in the female purview, and here most obviously connected to lunar cycles.

Purification and Pardoning

As Tlazolteotl-Tlaelquani, she is the “Eater of Excrement”, the pardoner of sins. Sahagún writes that the old or terminally ill would seek Her because this absolution could only be given once in a lifetime. Her clergy would not only hear confessions and grant absolution but would also find those, especially adulterers, who did not confess and bring them to public punishment. Tlazolteotl was invoked at a new birth, to cleanse a baby of her parents’ transgressions.

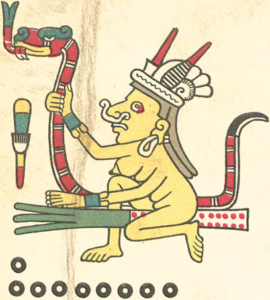

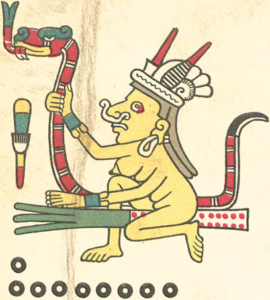

From the Tonalamatl de los Pochtecas comes a lovely image of Tlazolteotl. She is nude, wearing an elaborate headdress, and riding a broom. Her  headdress includes the usual spools of unspun cotton, as well as a shell, showing her ties with the lunar cycles. She is drawn with a wrinkled paunch, symbolic of a woman who has given birth. She holds a red snake, symbol of the fertility of menstrual flow (Baéz-Jorge 100) The broom is a reference to the Aztec purification festival of Ochpaniztli, which honored the female deities, including Tlazolteotl.

headdress includes the usual spools of unspun cotton, as well as a shell, showing her ties with the lunar cycles. She is drawn with a wrinkled paunch, symbolic of a woman who has given birth. She holds a red snake, symbol of the fertility of menstrual flow (Baéz-Jorge 100) The broom is a reference to the Aztec purification festival of Ochpaniztli, which honored the female deities, including Tlazolteotl.

As Tlazolteotl-Tlaelquani, She was the Goddess of the black, fertile earth, the rotting earth, the fecund earth that gains its energy from death, and in turn feeds life. Associated with purification, expiation, and regeneration, She turns all garbage, physical and meta-physical, into rich life.

Embodying the cycle

Tlazolteotl, Goddess of Cotton, Goddess of Filth, Eater of Excrement. She is the regenerative power of the earth, the midwife, and the pardoner. One of the most provocative renditions of Tlazolteotl is from the Codex Borbonicus (see image at top). She squats in the birth-giving position, wearing the conical Huastec hat with tassels, similar to the tassels on new corn. She wears black and red, decorated with crescent moons which, to my eye, mimic the shape of a vulva.

This drawing shows Tlazolteotl conceiving a child (see the child coming from above and to the right, footprints leading to the place of conception, the head), and She births a child who wears a headdress, earrings, and necklace just like her mother. While embodying this cycle of life, Tlazolteotl wears the flayed skin of the sacrificial victim (the dimpled skin always signifies this, but it is very obvious here with the extra hands hanging below), a symbol of death feeding life.

Tlazoteotl is associated with the trecena beginning with Ce Ollin, 1 Movement. The glyph for ollin shows the combining of two elements to form movement, symbolizing the active principle. The symbol for ollin is here as well in the two snakes to the right — one fleshed and the other discarnate. The two, intertwined, convey in vivid detail the interdependence of death and life.

In this image, She is the cycle of death and life, of death feeding life, of life cycling to death. The twinned snakes encapsulate ollin, the movement of life. Tlazolteotl is the provoker and the pardoner, the active female principle in the continual cycle of death and life.

Notes

- All translations from the Spanish are my own.

- A trecena is a 13-day period of time in the ritual calendar (the Tonálpohualli). The entire 260-day ritual calendar cycle consists of 20 “months” of 13 days each. The name trecena comes from trece, which is Spanish for thirteen.

- The Mesoamericans recorded their history and lore in a pictographic/logographic language drawn on long strips of paper referred to as “codices” (sing. codex). The paper, often made from deer hide, bark, or reeds, was whitewashed, allowing the full color of the graphics to be shown. The codices were often written on both sides of a long strip, and then folded accordion-style. The name of a codex often refers to its present location or owner. For example, the Codex Borgia was owned by Cardinal Borgia; it presently resides in the Vatican.

- “Massage and binding is a traditional postpartum ritual practiced by the Maya women in the Yucatan…. In the final stage of the massage process, another female relative (usually the mother-in-law) helps the midwife by laying the binder over the abdomen and passing the ends to each other under the small of her back. The binder is cinched around the pelvis as tightly as the woman can stand it.” Fuller, Nancy and Brigitte Jordan. “Maya Women and the End of the Birthing Period: Postpartum Massage-and-Binding in Yucatan, Mexico”. Medical Anthropology, 5(1): 35-50, 1981

- Bitumen was chewed by men only in private. Men publicly chewing bitumen were considered homosexuals.

- See McCafferty and McCafferty for a full examination of women and weaving.

Bibliography

- Báez-Jorge, F. (1988). Los oficios de las diosas [The stations of the goddesses]. Xalapa, Universidad Veracruzana.

- Fernandez, A. (1999). Dioses Prehispanicos de Mexico. Mexico City, Panorama Editorial.

- Klein, C. “Teocuitlatl, ‘Divine Excrement’: The Significance of ‘Holy Shit’ in Ancient Mexico. Art Journal, Vol. 52, No. 3, Scatological Art (Autumn, 1993), pp. 20-27.

- McCafferty, S.D. and G. G. McCafferty (1991). “Spinning and Weaving as Female Gender Identity in Post-Classic Mexico.” In Textile Traditions of Mesoamerica and the Andes: An Anthology, edited by M. Schevill, J.C. Berlo, and el. Dwyer, pp. 19-44. Garland, New York.

- Sahagún, B. (1999). Historia general de las cosas de nueva España [General history of things of New Spain] (A. M. Garibay K., Trans.). Mexico City, Editorial Porrúa. (Original work published 1829).

- Sullivan, T. “Tlazolteotl-Ixcuina: The Great Spinner and Weaver”. The Art and Iconography of late post-Classic Mexico, Ed. Elizabeth Hill Boone. Dumbarton Oaks, Washington DC. pp. 7-37.

Originally Published in Matrifocus.

by Anne Key | Mar 7, 2017 | Mesoamerican Goddesses

The cosmology of the Mesoamericans presents a lush, complex landscape of deities and ideas. Study of this cosmology, through a particularly feminist lens, reveals powerful female deities. Among the most intriguing are the Cihuateteo[1].

The Cihuateteo (literally “women goddesses”)[2] appear in the pantheon of Mesoamerican cosmology as mortal women who died in childbirth and were then deified[3]. In regular cycles, the Cihuateteo traversed the heavens, the underworld, and the earthly plane. Daily they dwelt with the stars in the western sky in the heavenly region called Cihuatlampa (“place of women”) and accompanied the sun from noon to sunset, then through the night as it lit the underworld[4]. Every 52 days[5] in the ritual calendar[6], the Cihuateteo descended to earth to reign for a day associated with the west. It is the very regularity of the Cihuateteo’s presence that places them habitually in the lives of the Mesoamericans.

In central Mexico, Goddesses were worshipped at cihuateocalli (“goddess houses”) of different sizes and locations. The Cihuateteo were honored in neighborhood cihuateocalli built at the crossroads. During the days of the Goddesses’ descent, their images in the shrines were festooned with paper (amatetéuitl) pegged to the statues with bits of rubber or copal[7]. They were given offerings of tamales[8] and toasted corn, as well as bread shaped as butterflies and lightning rays.

On the days the Cihuateteo descended, children were cautioned to stay inside and men were warned to be careful, as contact with these Goddesses could cause palsy. These admonitions have historically been used to paint the Cihuateteo as maleficent beings. I offer another interpretation, seeing the days they descended as times when possession was imminent and viewing palsy as a symptom of possession. Only those who were skilled in dealing with divine possession should be outside on the days the Cihuateteo descended.

The negative framing of these Goddesses has led to their continued demonization. Modern writings compare them to vampires and other maleficent specters. However, according to the veneration practices of the Mesoamericans, the Cihuateteo are powerful, benevolent and munificent ancestors.

One of the most beautiful tributes to the Cihuateteo was the prayer that the midwife recited at the death of a young mother.[9] In this prayer the midwife cried at the death of her patient, urging the parents to be glad that their child had died in childbirth because she would become a Goddess and accompany the sun as a brave one, a mocihuaquetzque[10]:

My little one, my daughter, my noble woman, you have wearied yourself, you have fought bravely. By your labors you have achieved a noble death, you have come to the place of the Divine. …Go, beloved child, little by little towards them (the Cihuateteo) and become one of them; go daughter and they will receive you and you will be one of them forever, rejoicing with your happy voices in praise of our Mother and Father, the Sun, and you will always accompany them wherever they go in their rejoicing. (Sahagún 381-382)

At the end of the prayer, the midwife exhorted the new Cihuateotl not to forget her and all those left on earth, to remember and aid them as they led their hard lives on the earthly plane. This prayer portrayed the Cihuateteo as benevolent beings, honored and revered.

Throughout this prayer, the Cihuateteo were referred to in militaristic terms. They were called “brave” and extolled for “fighting bravely”, and their daily journey with the sun from noon to dusk mirrored the slain warrior’s journey with the sun from dawn to noon. The Cihuateteo were literally the embodiment of bravery. In fact, warriors would attempt to sever the middle finger of the dead woman’s left hand to use as a talisman to assure their own bravery and success in battle. The midwives and family members who carried her to her grave had to stop warriors from dismembering the body of the Cihuateteo.

The question of why the Cihuateteo were described in militaristic terms and venerated in the same way as warriors who died in battle has been much debated. Melgarejo Vivanco wrote that the Cihuateteo were given the same honor as dead warriors because it helped promote motherhood “with the incentive of deification” (167). A militaristic society, he noted, must be supplied with soldiers. This is a commonly repeated theory.

|

|

Cihuateotl. Provenance: Mexico City. Note the skeletolized face and clawed fingers (clawed toes not visible). Belt around waist has similar ollin style knot.

Photo © Anne Key.

|

However, honoring women by comparing them to warriors assumes that warriors had died in battle before women died in childbirth[11]. I suggest that the scenario of the Cihuateteo existed before the culture knew war[12], and that the increasingly militaristic Mesoamerican society may have co-opted a longstanding custom of honoring women who died in childbirth to valorize its practices.

It can then be posited that warriors were given the same status as women who died in childbirth; that as an incentive for warriors to go into battle, they were to be honored as women had been honored for centuries, perhaps millennia. Women dying in childbirth were the exemplars of courage, given the highest honor available to mortals — to journey with the sun. Warriors would share this honor, giving them the same status as the Cihuateteo.

The iconography associated with the Cihuateteo differs in the various regions. The Cihuateteo statues from the state of Veracruz were modeled after the deceased bodies of individual women who died in childbirth. Multivalent symbols appear on these statues: fantastic headdresses represent the sky dragon and the earth monster; bicephalic pit-vipers wrapped around their waists represent internal female organs and attributes of deities associated with death. The vipers are tied in a knot similar to the glyph ollin, which means “movement”.

The most striking aspect of these statues is their humanness. These were real women — the artisans’ contemporaries, possibly their relatives, friends, part of their community. They were rendered as fleshy, corporeal, mortal, real. Every post-mortem detail was captured. I believe it is this humanness that makes these statues a true testament to the deceased women — they were truly revered ancestors.

In contrast, the Central Mexican Cihuateteo do not have individual characteristics; there is little variance among them. These statues are kneeling and have descarnated faces and clawed feet, contrasted with their long, luxurious hair. On the top of some of their heads, a day glyph of one of the days of the Cihuateteo’s descent is designed into the hair. Their belts or snakes are tied in the similar ollin glyph style knot. Their breasts are bared, visible above their knotted belts and skirts.

The Cihuateteo were the beloved and brave women who died in the act of childbirth. The midwife’s prayer assured the mother that her death had not been in vain, that she would be remembered for her act of bravery. The prayer poignantly expressed the bravery of the Cihuateteo, showing their honored place with the sun. There was no doubt that the Cihuateteo were powerful deities. Traversing the celestial, earthly, and underworld spheres and honored in neighborhood shrines, they were an integral part of the spiritual landscape of the Mesoamericans.

Notes

- All translations from the Spanish or Nahuatl are mine.

- Cihuateteo (pl); Cihuateotl (sing).

- See Pomeroy for speculation that Spartan women who died in childbirth were also honored in the same way as warriors slain in battle.

- The underworld portion of this cycle is not explicitly stated in Sahagún’s writings but can be found elsewhere. See Key for evidence and sources.

- The 260-day ritual year was divided into 20 time periods called trecenas (from the Spanish trece meaning 13) made up of 13 days each. There were four sets of trecenas, each associated with one of the four directions. So in the whole 260-day cycle, five individual trecenas were associated with a single direction. The Cihuateteo descended on the first day of each trecena associated with the west: the 3rd, ce mazatl (one deer); the 7th, ce quiahuitl (one rain); the 11th, ce ozomatl (one monkey); the 15th, ce calli (one house); and the 19th, ce quauhtli (one eagle).

- It has been suggested that this 260-day ritual cycle follows the human gestation period from the first sign of life to birth (covering 9 lunations) and is intricately associated with female cycles. See Tate for further information.

- Copal is a fragrant tree resin burned in ritual. It is still used today.

- Tamales are still considered sacred food, made and served on feast days. Tamales represent the human body: the masa(corn dough) is the skin, the meat is the muscle, and the red sauce is the blood.

- Many prayers and rites of the Aztecs were recorded by B. Sahagún, one of the first clerics to arrive in Mexico from Spain. He recorded the Prayer of the Midwife in a romanized version of the indigenous oral language Nahuatl. Though his writings are certainly infused with a Catholic overlay, they are one of the few extant sources for pre-conquest rituals, prayers, and beliefs. For a beautiful rendition of many of the sacred sayings and prayers, see Sullivan and Knab.

- This term is sometimes translated as “brave ones”, “valiant women” or “female warriors” and other times as “those that arose as women”. See Miller and Taube and Klein.

- Rohrlich and Nash find “no evidence of gender and class distinctions, or of warfare, before the latter part of Toltec hegemony” (p. 93), possibly as late as 900 CE. However, more current scholarship by Marcus finds signs of warfare in the Oaxaca area by 700-500 BCE. According to Marcus, from 1400 to 1150 BCE the society was egalitarian, with families “integrated through participation in village ritual” (p. 2). However, signs of hereditary inequality began appearing in 1150 BCE, and by 700-500 BCE, warfare was evident.

- de Piña Chán speculates that the Cihuateteo date from the Formative era but that they do not appear in statuary until the Classic era on the Gulf Coast (p. 152).

Works Cited

- Key, Anne. Death and the Divine: The Cihuateteo, Goddesses in the Mesoamerican Cosmovision. Diss. California Institute of Integral Studies, 2005.

- Klein, Cecilia. “The devil and the skirt: An iconographic inquiry into the pre-Hispanic nature of the Tzitzimime”. Ejournal: Revista estudios de cultural Náhuatl. 31 (2000): April 20, 2003, http://www.ejournal.unam.mx/cultura_nahuatl/ecnahuatl31/ECN31002.pdf.

- Marcus, J. Women’s Ritual in Formative Oaxaca: Figurine-making, Divination, Death, and the Ancestors. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. 1988

- Melgarejo Vivanco, J. L. Los Totonaca y su cultura [The Totonacs and their culture]. Xalapa, Mexico: Universidad Veracruzana. 1985.

- Miller, Mary and Karl Taube. The Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. New York: Thames and Hudson. 1993.

- de Piña Chán, Beatriz.B. “ Elementos psicopompos en la arqueología mexicana [Psychopomp elements in Mexican archaeology]”. Ed. H. K. Kocyba, Y Gonález Torres, & R. Piña Chán Historia comparativa de las religiones Mexico City, Mexico: INAH. 1988. 145-168.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. Spartan Women. New York: Oxford University Press. 2002.

- Rohrlich, R., & Nash, J. “The patriarchal puzzle: State formation in Mesopotamia and Mesoamerica”. (No publication information available.) 1981. 90-95.

- Sahagún, Bernardino. Historia general de las cosas de nueva españa. Transl. A.M. Garibay K. Mexico City: Editorial Porrúa. 1999.

- Sullivan, Thelma D. and Timothy J. Knab. A Scattering of Jades: Stories, Poems, and Prayers of the Aztecs. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. 2003.

- Tate, Carolyn. “Writing on the Face of the Moon”. Manifesting Power: Gender and the Interpretation of Power. Ed. Tracy Sweely. New York: Routledge. 1999. 81-102

Graphics Credits

Cihuateteo, photos © 2008 Anne Key. All rights reserved.

This post first appeared in Matrifocus.

by Anne Key | Mar 7, 2017 | Mesoamerican Goddesses

In 2006, another giant monolith was found at the Templo Mayor in Mexico City. Like the Coatlicue monolith found decades earlier, this new discovery also towers at over seven feet tall. She is Tlaltecuhtli, the Earth Goddess.

Images of Tlaltecuhtli are often found carved on the bottom of Aztec sculptures — where the sculpture comes in contact with the earth. The most famous  of these images is the one on the bottom of the giant Coatlicue from the Templo Mayor in Mexico City. Representations of Tlaltecuhtli are found at the murals of Teotihuacan, a ceremonial center near modern-day Mexico City.

of these images is the one on the bottom of the giant Coatlicue from the Templo Mayor in Mexico City. Representations of Tlaltecuhtli are found at the murals of Teotihuacan, a ceremonial center near modern-day Mexico City.

Her name literally means “earth-lord” (Tlal =land; cuhtli = lord).[1] While the suffix of her name connotes male gender, she appears in myth as female and her pictorial representation is decidedly female, usually in the birth-giving posture. Midwives prayed to Tlaltecuhtli in the cases of difficult birth. Also she was invoked as the Sun in prayers to another Aztec deity, Tezcatlipoca (Miller 168). Tlaltecuhtli is the Earth Goddess, part of the Central Mexican pantheon, and her image stretches into the Mayan territories.

Image and Meaning

One of Tlaltecuhtli’s most distinctive features is her gaping maw, showing flint knives[2] for teeth and a protruding tongue. Her hands and feet are often clawed, bringing to mind both predatory birds and carrion-eaters. Above she is pictured with skull masks at her elbows and feet as well as in her hands. Her birth-giving posture connects her to frog imagery.

from: http://www.revista.unam.mx/vol.12/num4/art38/

The open mouth of the Tlaltecuhtli can be seen as a tomb — or as a womb. On the first page from the Tonalámatl de los Pochtecas the Earth Goddess appears, jaws wide, teeth exposed. Out of her mouth grows the tree of life. The tree of life growing from these jaws of death completes this picture of the earth as womb and tomb, and of the mouth and eating as analogous to birth and death.

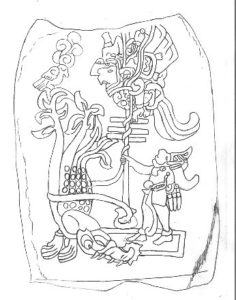

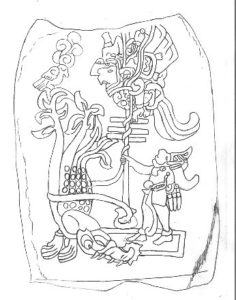

Images of the Earth Goddess appear in Maya iconography as well. In the Mayan ceremonial complex of Izapa, Stele 25 shows the Earth Goddess as a crocodile, arranged vertically, pointing headfirst towards the

By http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%94%BB%E5%83%8F:Izapa_stela25.JPG, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=588150

ground with her tail becoming a tree.[3] These are two beautiful symbols of the creative force of the earth as represented by the Earth Goddess, connecting her with trees, the firmament, and the act of creation either out of her own mouth or with her own body. The Izapan style Earth Goddess represents the earth and death and the “dynamics between death and birth that govern the universe”, according to De la Garza (2002, p. 98), who identifies the symbolism of the Earth Goddess or, as she terms it, the “Terrestrial Dragon” as linking life and death:

Considering its relationship with the earth, the dragon symbolized the earthly surface, as well as the generating power hidden inside. Thus it is linked with the death god who dwells there, the jaguar, who is a symbol of the dead Sun, the netherworld, and the night sky.(122)

The Earth Goddess resembles a crocodile here but has also been identified in both English and Spanish interpretations as a variety of beings: snake, alligator (caimán), crocodile or lizard (lagarto or lagartija), dragon, and mythical monster/creature. Whatever species, mythical or real, that the Earth Goddess represents, she unites both telluric and aquatic aspects.

The image of the caimán corresponds to the day-sign Cipactli. Ce Cipactli (one-caimán), is the first day of the 260-day ritual calendar. As the ritual calendar can represent the cycle of human life, Cipactli represents the beginning of life. Tlaltecuhtli is the maw of life and death, the mouth that is womb and tomb. And as we will see in the following myth, she is the incarnation of the earth.

Myth

The Earth Goddess is associated with the very creation of the earth. She stands as a symbol of telluric creation and as a symbol of the creative capacity of the earth. In myths and the codices, the Earth Goddess in her form as Cipactli literally becomes the earth; she is a primordial sea creature whose dismembered body forms the earth.

From the 16th century manuscript Histoyre du Mechique comes the myth of the creation of the earth (Markman 213). In this myth, the two gods Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca carried Tlaltecuhtli from heaven to earth. When they arrived on earth, they found it covered with water and realized they needed to create land. The two gods changed themselves into two snakes and seized Tlaltecuhtli by the hands and feet and pulled her with such force that she was severed. Her body from her shoulders down became the earth, and from the shoulders up it became the heavens.

The other deities were extremely upset by the actions of these two gods. In order to recompense Tlaltecuhtli, all the gods arrived on earth to console her and deemed her the source of all sustenance:

And in order to do this, they made from her hair trees and flowers and grasses, from her skin the very fine grass and small flowers, from her eyes wells and fountains and small caverns, from her mouth rivers and great caverns, from her nose mountain valleys, and from her shoulders mountains. And this goddess sometimes wept at night, desiring to eat men’s hearts, and would not be quiet until they were offered to her, nor would she bear fruit unless she was watered with the blood of men. (Markman 213)

This myth has a blatantly misogynistic overlay, possibly from the original manuscript by a Spanish chronicler (which has since been lost) or by the French translator, or by the orator himself. Certainly this view is limited: The earth as an unwilling participant in creation and the reciprocal relationship of human to earth as based in sadness and anger.

However, the underlying storyline shows Tlaltecuhtli as the earth; the earth is literally the Goddess incarnate. Her body is the contours of the land, and all nourishment and sustenance come from her.  Commenting on this myth, Carrasco likens the theme of dismemberment to the act of creation: “This combination of dismemberment and creation is an emphatic characteristic of Mesoamerican mythology. The creation of the world is constantly joined in the destruction of the world in mythic narratives” (440). Viewed through a different lens, one where the dismemberment happens willingly, the earth is the gift of the Goddess, and the reciprocal sacrifice that humans offer is their gift to her.

Commenting on this myth, Carrasco likens the theme of dismemberment to the act of creation: “This combination of dismemberment and creation is an emphatic characteristic of Mesoamerican mythology. The creation of the world is constantly joined in the destruction of the world in mythic narratives” (440). Viewed through a different lens, one where the dismemberment happens willingly, the earth is the gift of the Goddess, and the reciprocal sacrifice that humans offer is their gift to her.

Báez-Jorge sees the Earth Goddess as the center of a quadripartite group of deities: Cóatlicue as the origin of the celestial deities; Chicomecóatl as the provider of sustenance; Cihuacóatl as motherhood and death;and Chalchiuhtlicue as controlling terrestrial waters. In the center is the Earth Mother, the “sacred essence that incorporates the totality of the numinous characteristics that are dialectically linked (human fertility and vegetation; life and death; phases of the moon, etc.) and in turn that which is realized by an internal connection that unifies these distinct responsibilities” (132-133).

The Jaws of Life and Death

Tlaltecuhtli is the earth incarnate, the in-carn-ation of the earth; the earth made flesh. The Earth Goddess embodies the duality of creation and death. The Goddess has her mouth open to give and receive in reciprocal relationship with those who dwell in her.

A song from the Nahua peoples of San Miguel in Sierra del Puebla beautifully portrays this relationship of earth and human. The earth, the most holy earth, is the source of life for the people of San Miguel. As they themselves say here:

We live HERE on this earth (stamping on the mud floor)

We are all fruits of the earth

The earth sustains us

We grow here, on the earth and lower

And when we die, we wither on the earth

We are ALL FRUITS of the earth (stamping on the mud floor).

We eat of the earth

Then the earth eats us. (Broda 107)

Notes

- All translations from the Spanish are mine.

- As the primary means of striking fire, flint was symbolic of the debt humans owed to the deities for sustenance and life. Flint knives were associated with sacrifice and were often personified, adorned with eyes and mouths.

- For a fuller treatment of this stele, see de la Garza 2002.

Bibliography

- Báez-Jorge, F. (1988). Los oficios de las diosas [The offices of the goddesses]. Xalapa, Mexico: Universidad Veracruzana.

- Broda, J. (1987). “Templo Mayor as Ritual Space”. In J. Broda, D. Carrasco, and E. Matos Moctezuma The Great Temple of Tenochtitlan: Center and Periphery in the Aztec World. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 61-123.

- Carrasco, D. (1995) “Cosmic Jaws: We eat the Gods and the Gods Eat Us.” In Journal of the American Academy of Religion. Vol. 63. No. 3, pp. 429-463.

- Coe, M. D. (1997). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Garza, M. de la. (1998). El universo sagrado de la serpiente entre los Mayas [The sacred universe of the serpent according to the Mayas]. Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Markman, R. and P. Markman (1992). The Flayed God: The Mesoamerican Mythological Tradition. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

- Miller, M. and K. Taube. (1993). An Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

- Pasztory, E. (1998). Pre-Columbian Art. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Sahagún, B. (1999). Historia general de las cosas de nueva España [General history of things of New Spain] (A. M. Garibay K., Trans.). Mexico City, Mexico: Editorial Porrúa. (Original work published 1829; written in the 16th century)

- Tate, Carolyn. “Writing on the Face of the Moon”. Manifesting Power: Gender and the Interpretation of Power. Ed. Tracy Sweely. New York: Routledge, 1999. 81-102. Challenging Secularization.Aldershot, UK and Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Originally published Lammas 2009 on Matrifocus.com.

eagle feathers in her hair, attesting to her bravery and courage. A large ceremonial headdress sits atop her head, and her ears are adorned with pendulous earrings. A “warrior’s belt knotted from a double headed snake” winds around her waist (Kroger 189). Her belly is puckered, showing that she has given birth. She is a mother and a warrior.

eagle feathers in her hair, attesting to her bravery and courage. A large ceremonial headdress sits atop her head, and her ears are adorned with pendulous earrings. A “warrior’s belt knotted from a double headed snake” winds around her waist (Kroger 189). Her belly is puckered, showing that she has given birth. She is a mother and a warrior. The giant stone sculpture of Coyolxauhqui was found at the foot of the stairs of the Templo Mayor, on the side dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. It may have been hurtled down the stairs, just as she was thrown from Coatepec. While it may have been put there as a symbol of defeat, the sheer size of it is a reminder of the threat she presented.

The giant stone sculpture of Coyolxauhqui was found at the foot of the stairs of the Templo Mayor, on the side dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. It may have been hurtled down the stairs, just as she was thrown from Coatepec. While it may have been put there as a symbol of defeat, the sheer size of it is a reminder of the threat she presented. Special Introductory price for the Jade Oracle deck:

Special Introductory price for the Jade Oracle deck: Priestess, instructor, writer and dancer – Anne Key, Ph.D. has traveled, researched, and written about Mesoamerican culture since 1990; her dissertation investigated the pre-Hispanic divine women known as the Cihuateteo, and she is co-founder and guide for Sacred Tours of Mexico. She was Priestess of the Temple of Goddess Spirituality Dedicated to Sekhmet, located in Nevada and has edited anthologies on women’s spirituality, priestesses, and Sekhmet as well as written two memoirs, Desert Priestess: a memoir and Burlesque, Yoga, Sex and Love. An adjunct faculty in Women’s Studies, English and Religious Studies, she is co-founder of the independent press Goddess Ink. Anne resides in Albuquerque with her husband, his two cats and her snake, Asherah.

Priestess, instructor, writer and dancer – Anne Key, Ph.D. has traveled, researched, and written about Mesoamerican culture since 1990; her dissertation investigated the pre-Hispanic divine women known as the Cihuateteo, and she is co-founder and guide for Sacred Tours of Mexico. She was Priestess of the Temple of Goddess Spirituality Dedicated to Sekhmet, located in Nevada and has edited anthologies on women’s spirituality, priestesses, and Sekhmet as well as written two memoirs, Desert Priestess: a memoir and Burlesque, Yoga, Sex and Love. An adjunct faculty in Women’s Studies, English and Religious Studies, she is co-founder of the independent press Goddess Ink. Anne resides in Albuquerque with her husband, his two cats and her snake, Asherah.

Commenting on this myth, Carrasco likens the theme of dismemberment to the act of creation: “This combination of dismemberment and creation is an emphatic characteristic of Mesoamerican mythology. The creation of the world is constantly joined in the destruction of the world in mythic narratives”

Commenting on this myth, Carrasco likens the theme of dismemberment to the act of creation: “This combination of dismemberment and creation is an emphatic characteristic of Mesoamerican mythology. The creation of the world is constantly joined in the destruction of the world in mythic narratives”