Coyolxauhqui: She Who Is Adorned with Bells by Anne Key

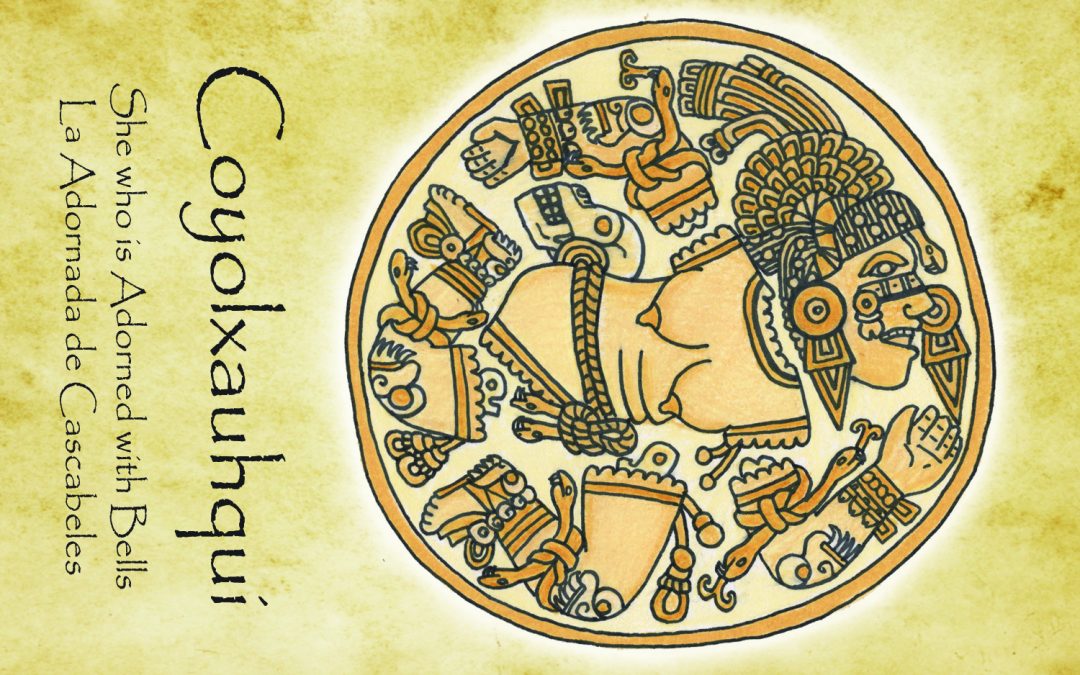

One of the most fascinating deities of pre-Columbian Mexico is Coyolxauhqui. At first glance, a deity named “She Who is Adorned with Bells” might seem to be a dancer, until we read that warriors wrapped strings of bells around their calves before going to battle. Then we see Coyolxauhqui (Nahuatl: coyolli = small metal bells) as a warrior, suiting up for battle.

The image of Coyolxauhqui is beautifully rendered in the massive stone relief that was found at the Great Temple (Templo Mayor). Construction of this temple began in 1325 CE, and it was the main temple of worship for the Aztecs in their capital of Tenochtitlan (present-day Mexico City). The Templo Mayor was dedicated to two deities, Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli. Tlaloc (Lord of rain) was most likely a local deity before the Aztecs arrived. Huitzilopochtli (Left Hummingbird) was the warrior deity of the Mexica, accompanying them on their sojourn from northern Mexico to Tenochtitlan, which resides in the altiplano, or high plains, of central Mexico. The Templo Mayor may have been a symbolic representation of the Hill of Coatepec, recounting the story of Huitzilopochtli’s birth and Coyolxauqui’s demise.

The Templo Mayor was a large structure at 328’ x 262’ at its base. Rebuilt six times, its excavated ruins are on the northeast edge of the zócalo, or city center, of Mexico City. The Spanish used the stones from the temple to build what is now known as the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral, a massive structure situated atop the Templo Mayor. But careful excavation, and some lucky breaks, have brought both the temple and many of its monolithic sculptures to light.

In February of 1978, while workman for an electrical company were digging, they discovered the giant disk of Coyolxauhqui. The stone disk is 10.7 feet in diameter, almost a foot thick, and weighs over 9 tons. Her discovery set off a wave of archaeological work on the Templo Mayor.

Coyolxauhqui is the second largest sculpture found in the temple. This exquisitely carved disk encircles her. She is dressed in full battle gear with balls of eagle feathers in her hair, attesting to her bravery and courage. A large ceremonial headdress sits atop her head, and her ears are adorned with pendulous earrings. A “warrior’s belt knotted from a double headed snake” winds around her waist (Kroger 189). Her belly is puckered, showing that she has given birth. She is a mother and a warrior.

eagle feathers in her hair, attesting to her bravery and courage. A large ceremonial headdress sits atop her head, and her ears are adorned with pendulous earrings. A “warrior’s belt knotted from a double headed snake” winds around her waist (Kroger 189). Her belly is puckered, showing that she has given birth. She is a mother and a warrior.

Looking closely at her stone relief, we see a curious space between her limbs and torso, between her neck and head. Her arms and legs, attired with the pads and bindings of a warrior, are dismembered. A bit of bone sticks out from each thigh and upper arm. Her head is also separated from her body, almost unnoticeable. Even dismembered, she is resplendent with dynamic warrior energy, the circular stone emphasizing her strength, evoking the idea that she is hurtling forward.

When I stand in front of her, in the museum at the Templo Mayor, the first emotion I feel is strength and bravery. Her dismemberment does nothing to diminish her power, for she continues on in spite of all the odds. She is unstoppable.

When I meet her in visions, Coyolxauhqui barely has time for me. She is surrounded by training warriors, shouting directions and giving orders. She looks me straight in the eye and says “don’t you dare make me fit into whatever story you want to tell.” She requires me to tell her story, unapologetically.

She exudes the power and potency of warrior women, both mythic and contemporary: Boudica, Athena, Joan of Arc, Hyppolita, Atalanta, Wonder Woman, Xena, and Trinity.

Unfortunately, the myth of Coyolxauhqui is not in her own words. The story we have of her is one that reinforces a patriarchal worldview, showing favor on women who are kind, all-loving “mothers” and killing upstart rebels. This is a pattern we know well.

When I approach the story of Coyolxauhqui, I work to find the “back story,” to fill out the entire narrative sequence. We will start with the myth as it was written by the Spanish cleric Bernardino Sahagún in The Florentine Codex. This mytho-historic account begins, and ends, with Huitzilopochtli, for this story, written by the victors, can be read as a myth explaining how the Mexica inserted their deity into the local lore, and how he was victorious.

This mytho-historical saga takes place during the migration of peoples from Aztlán, the ancestral home of the peoples that came to live in the place that is now Mexico City. Aztlán was possibly located in northern Mexico or the Southwest of the United States, and the migratory groups consisted of many tribes, including the Mexica. Along the way, the migrating group encountered many villages cultures, and one of these was the peoples of Coatepec.

The myth of the birth of Huitzilopochtli, which contains the only story of Coyolxauhqui, says very little of her strength, courage, and power. Instead, it paints her as the instigator of her mother’s assassination. Huitzilopochtli was a traditional Mexica deity, and he is the embodiment of male strength and warrior energy. He was one of the most celebrated deities of what would become the Aztec civilization.

The myth recalls a time during the migration from Aztlán when the people settled briefly at Coatepec, the “hill of the snake.” The deities living at Coatepec were Coyolxauhqui, her mother Coatlicue (She of the Serpent Skirt) and her 400 brothers (the Centzon Huitznahua). The myth opens with Coatlicue sweeping the temple.[1] She finds a bundle of precious feathers, picks them up, and keeps them underneath her clothes. These feathers make her pregnant.

When her sons, the 400 brothers, and her daughter, Coyolxauhqui, discover her pregnancy, they are enraged, saying that the pregnancy “insults us, dishonors us” (Markham 382). They ask her who fathered the child, but she does not answer. Coyolxauhqui leads the brothers in a plan to kill their mother, Coatlicue. While this seems a strong response, later we find out that the child in Coatlicue’s womb is Huitzilopochtli, the warrior deity of the migrant peoples, the Mexica.[2]

Meanwhile, Huitzilopochtli, from the womb of his mother, Coatlicue, tells her: “Do not be afraid, I know what I must do” (Markham 382).

In the myth, Coyolxauqui “incited them, she inflamed the anger of her brothers, so that they should kill their mother. And the four hundred gods made ready, they attired themselves as for war” (Markham 383), including tying bells (oyohualli) on the calves of their legs.

Let’s take a moment and unpack what has happened so far. We have a group of migratory Mexica bringing a new deity to an existing culture. This becomes the story of how Coyolxauhqui defended her land and culture from the Mexica, presenting her as the military leader, the defender. And, it paves the way for Huitzilopochtli to insert himself (literally!) into the myth of Coatepec, converting the primordial mother of the Coatepec culture into his birth mother and shaming their greatest warrior, Coyolxauhqui.

Returning to the myth, Coyolxauhqui is marshalling the troops for war. One of the 400 brothers, Cuahuitlicac, turns against the rest of his family and informs Huitzilopochtli (still in Coatlicue’s womb) of the plan of attack. At the moment Coyolxauhqui and the 400 brothers approach their mother, Huitzilopochtli is born in full battle gear. He takes the Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent, and strikes Coyolxauhqui, cutting off her head. Her body rolls down the hill of Coatepec, arms and legs separating as she falls.[3]

Huitzilopochtli drove the 400 brothers off Coatepec, slaughtering them. Some escaped to the south, but those killed by Huitzilopochtli were stripped of their “gear, their ornaments,” and Huitzilopochtli “took possession of them…introduced them into his destiny…made them his own insignia” (Markham 386).

This myth can be seen as a cautionary tale of women’s diminished power in the newly formed Aztec society. M. J. Rodríguez Shadow, in her book La Mujer Azteca, writes that there is ample evidence of matrilineal and matrifocal societies in Mesoamerica before the 14th century CE (1997, p. 68). However:

During the epoch of the Aztecs the religion glorified masculine values, erasing whatever vestige of that phase [matrifocal] existed, quickly and efficiently, replacing them with male gods and men, destroying allegorically the feminine figures (like Coyolxauhqui) that could have occupied positions of power or discrediting those [female figures] that they wanted to retain (like Malinalxóchitl).[4] (p. 69)

Moreover, in this myth Huitzilopochtli appropriates Coyolxauhqui’s warrior aspect. Art historian Janet Berlo puts this myth in context:

But one of the central myths of the Aztec empire is the struggle between the newly born male warrior god and the warrior goddess who preceded him. I believe this myth structurally embodies the ideological struggle between the Great Goddess of the Central Mexican past and the new Aztec order in which the significant ties of mythic kinship are redrawn to emphasize the male lines of Huitzilopochtli…. In this fraternal kinship network, the northern invaders and their ancestral god Huitzilopochtli are firmly linked with the Central Mexican past… (Berlo 1993)

The giant stone sculpture of Coyolxauhqui was found at the foot of the stairs of the Templo Mayor, on the side dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. It may have been hurtled down the stairs, just as she was thrown from Coatepec. While it may have been put there as a symbol of defeat, the sheer size of it is a reminder of the threat she presented.

The giant stone sculpture of Coyolxauhqui was found at the foot of the stairs of the Templo Mayor, on the side dedicated to Huitzilopochtli. It may have been hurtled down the stairs, just as she was thrown from Coatepec. While it may have been put there as a symbol of defeat, the sheer size of it is a reminder of the threat she presented.

On a personal note, living in these times, I feel like the dismembered Coyolxauhqui. I feel as if all I have worked for to make life better for myself, my students, my friends and neighbors in this great country is being dismembered. But, like Coyolxauhqui, I remain whole and strong. #metoo, #marchforourlives, #blacklivesmatter and so many more have grown from this fractured political environment. Coyolxauhqui is a testament to the power, strength, and resolve of those who have been defeated. In the Museum of the Templo Mayor where she resides, her spirit pervades the space, a permanent reminder of the warrior women and cultures that are in the earth and spirit of Central Mexico.

References:

Berlo, J. (1993). Icons and Ideologies at Teotihuacan: The Great Goddess Reconsidered. In J. C. Berlo (Ed.), Art, ideology, and the city of Teotihuacan (pp. 129-168). Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

Markman, R. H., Markman, P. T. (1992). The Flayed God: The Mesoamerican Mythological Tradition. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

Rodriguez Shadow, M. J. (1997). La mujer Azteca [The Aztec Woman]. Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México.

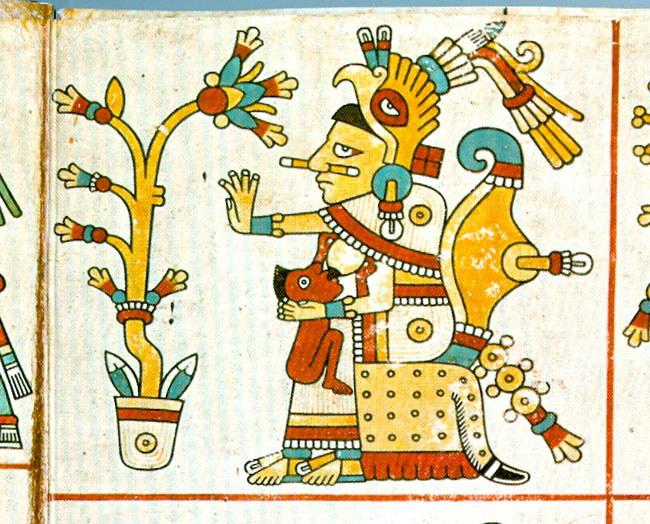

[1]Sweeping has a deeply ritual context for the ancient Mexicans. An entire festival, Ochpaniztli, was dedicated to sweeping the streets, private homes, and temples, preparing for harvest. Tlazohteotl, another Goddess, is shown with a broom, showing her connect to this festival.

[2]This brings up a number of different ideas. Did Coatlicue “change sides,” going against her people? Was she raped? Or did Coyolxauqui and her brothers know that if this god was allowed to birth through their mother, that it would be the end of Coatepec as they knew it?

[3]The statue of Coatlicue that once stood in the Templo Mayor replaces her arms with the Xiuhcoatl. Could it be possible that the Xiuhcoatl was a symbol of the culture at Coatepec, and that this was coopted by the migrating Mexica?

[4] En tiempos de los Aztecas la religion enaltecía los valores masculinos, borrando cualquiere vestigio de aquella fase y consolidando con eficacia y rapidez la sobresaliente posición de los dioses masculinos y los varones, destrozando alegóricamente las figuras femeninas (como Coyolxauhqui) que podia ocupar el poder o desacreditar a las que desearan compartirlo (como Malinalxóchitl).

Click here for more information on the Jade Oracle. Visit our Goddess Ink Media for videos about The Jade Oracle. For more information on Goddess Ink, visit our website and circle with us on Facebook and Instagram. Check out our newly designed store and please sign up for the Goddess Ink Newsletter for a monthly dose of inspiration. If you would like a weekday dose of daily inspiration sign up for our Daily Inspiration newsletter.

Special Introductory price for the Jade Oracle deck:

Special Introductory price for the Jade Oracle deck:

$45 until May 5th 2018 (Cinco de Mayo)! Find out more and purchase here.

Visit our Goddess Ink Media for videos about The Jade Oracle. For more information on Goddess Ink, visit our website and circle with us on Facebook and Instagram. Check out our newly designed store and please sign up for the Goddess Ink Newsletter for a monthly dose of inspiration. If you would like a weekday dose of daily inspiration sign up for our Daily Inspiration newsletter.

_______________________________________

Priestess, instructor, writer and dancer – Anne Key, Ph.D. has traveled, researched, and written about Mesoamerican culture since 1990; her dissertation investigated the pre-Hispanic divine women known as the Cihuateteo, and she is co-founder and guide for Sacred Tours of Mexico. She was Priestess of the Temple of Goddess Spirituality Dedicated to Sekhmet, located in Nevada and has edited anthologies on women’s spirituality, priestesses, and Sekhmet as well as written two memoirs, Desert Priestess: a memoir and Burlesque, Yoga, Sex and Love. An adjunct faculty in Women’s Studies, English and Religious Studies, she is co-founder of the independent press Goddess Ink. Anne resides in Albuquerque with her husband, his two cats and her snake, Asherah.

Priestess, instructor, writer and dancer – Anne Key, Ph.D. has traveled, researched, and written about Mesoamerican culture since 1990; her dissertation investigated the pre-Hispanic divine women known as the Cihuateteo, and she is co-founder and guide for Sacred Tours of Mexico. She was Priestess of the Temple of Goddess Spirituality Dedicated to Sekhmet, located in Nevada and has edited anthologies on women’s spirituality, priestesses, and Sekhmet as well as written two memoirs, Desert Priestess: a memoir and Burlesque, Yoga, Sex and Love. An adjunct faculty in Women’s Studies, English and Religious Studies, she is co-founder of the independent press Goddess Ink. Anne resides in Albuquerque with her husband, his two cats and her snake, Asherah.

Come see Coyolxauhqui and other wonders with Anne and Veronica Iglesias with Sacred Tours of Mexico!