In 2006, another giant monolith was found at the Templo Mayor in Mexico City. Like the Coatlicue monolith found decades earlier, this new discovery also towers at over seven feet tall. She is Tlaltecuhtli, the Earth Goddess.

Images of Tlaltecuhtli are often found carved on the bottom of Aztec sculptures — where the sculpture comes in contact with the earth. The most famous  of these images is the one on the bottom of the giant Coatlicue from the Templo Mayor in Mexico City. Representations of Tlaltecuhtli are found at the murals of Teotihuacan, a ceremonial center near modern-day Mexico City.

of these images is the one on the bottom of the giant Coatlicue from the Templo Mayor in Mexico City. Representations of Tlaltecuhtli are found at the murals of Teotihuacan, a ceremonial center near modern-day Mexico City.

Her name literally means “earth-lord” (Tlal =land; cuhtli = lord).[1] While the suffix of her name connotes male gender, she appears in myth as female and her pictorial representation is decidedly female, usually in the birth-giving posture. Midwives prayed to Tlaltecuhtli in the cases of difficult birth. Also she was invoked as the Sun in prayers to another Aztec deity, Tezcatlipoca (Miller 168). Tlaltecuhtli is the Earth Goddess, part of the Central Mexican pantheon, and her image stretches into the Mayan territories.

Image and Meaning

One of Tlaltecuhtli’s most distinctive features is her gaping maw, showing flint knives[2] for teeth and a protruding tongue. Her hands and feet are often clawed, bringing to mind both predatory birds and carrion-eaters. Above she is pictured with skull masks at her elbows and feet as well as in her hands. Her birth-giving posture connects her to frog imagery.

The open mouth of the Tlaltecuhtli can be seen as a tomb — or as a womb. On the first page from the Tonalámatl de los Pochtecas the Earth Goddess appears, jaws wide, teeth exposed. Out of her mouth grows the tree of life. The tree of life growing from these jaws of death completes this picture of the earth as womb and tomb, and of the mouth and eating as analogous to birth and death.

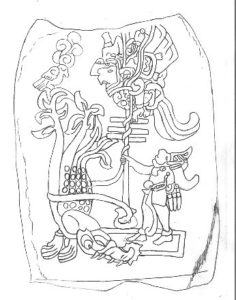

Images of the Earth Goddess appear in Maya iconography as well. In the Mayan ceremonial complex of Izapa, Stele 25 shows the Earth Goddess as a crocodile, arranged vertically, pointing headfirst towards the

By http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E7%94%BB%E5%83%8F:Izapa_stela25.JPG, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=588150

ground with her tail becoming a tree.[3] These are two beautiful symbols of the creative force of the earth as represented by the Earth Goddess, connecting her with trees, the firmament, and the act of creation either out of her own mouth or with her own body. The Izapan style Earth Goddess represents the earth and death and the “dynamics between death and birth that govern the universe”, according to De la Garza (2002, p. 98), who identifies the symbolism of the Earth Goddess or, as she terms it, the “Terrestrial Dragon” as linking life and death:

Considering its relationship with the earth, the dragon symbolized the earthly surface, as well as the generating power hidden inside. Thus it is linked with the death god who dwells there, the jaguar, who is a symbol of the dead Sun, the netherworld, and the night sky.(122)

The Earth Goddess resembles a crocodile here but has also been identified in both English and Spanish interpretations as a variety of beings: snake, alligator (caimán), crocodile or lizard (lagarto or lagartija), dragon, and mythical monster/creature. Whatever species, mythical or real, that the Earth Goddess represents, she unites both telluric and aquatic aspects.

The image of the caimán corresponds to the day-sign Cipactli. Ce Cipactli (one-caimán), is the first day of the 260-day ritual calendar. As the ritual calendar can represent the cycle of human life, Cipactli represents the beginning of life. Tlaltecuhtli is the maw of life and death, the mouth that is womb and tomb. And as we will see in the following myth, she is the incarnation of the earth.

Myth

The Earth Goddess is associated with the very creation of the earth. She stands as a symbol of telluric creation and as a symbol of the creative capacity of the earth. In myths and the codices, the Earth Goddess in her form as Cipactli literally becomes the earth; she is a primordial sea creature whose dismembered body forms the earth.

From the 16th century manuscript Histoyre du Mechique comes the myth of the creation of the earth (Markman 213). In this myth, the two gods Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca carried Tlaltecuhtli from heaven to earth. When they arrived on earth, they found it covered with water and realized they needed to create land. The two gods changed themselves into two snakes and seized Tlaltecuhtli by the hands and feet and pulled her with such force that she was severed. Her body from her shoulders down became the earth, and from the shoulders up it became the heavens.

The other deities were extremely upset by the actions of these two gods. In order to recompense Tlaltecuhtli, all the gods arrived on earth to console her and deemed her the source of all sustenance:

And in order to do this, they made from her hair trees and flowers and grasses, from her skin the very fine grass and small flowers, from her eyes wells and fountains and small caverns, from her mouth rivers and great caverns, from her nose mountain valleys, and from her shoulders mountains. And this goddess sometimes wept at night, desiring to eat men’s hearts, and would not be quiet until they were offered to her, nor would she bear fruit unless she was watered with the blood of men. (Markman 213)

This myth has a blatantly misogynistic overlay, possibly from the original manuscript by a Spanish chronicler (which has since been lost) or by the French translator, or by the orator himself. Certainly this view is limited: The earth as an unwilling participant in creation and the reciprocal relationship of human to earth as based in sadness and anger.

However, the underlying storyline shows Tlaltecuhtli as the earth; the earth is literally the Goddess incarnate. Her body is the contours of the land, and all nourishment and sustenance come from her.  Commenting on this myth, Carrasco likens the theme of dismemberment to the act of creation: “This combination of dismemberment and creation is an emphatic characteristic of Mesoamerican mythology. The creation of the world is constantly joined in the destruction of the world in mythic narratives” (440). Viewed through a different lens, one where the dismemberment happens willingly, the earth is the gift of the Goddess, and the reciprocal sacrifice that humans offer is their gift to her.

Commenting on this myth, Carrasco likens the theme of dismemberment to the act of creation: “This combination of dismemberment and creation is an emphatic characteristic of Mesoamerican mythology. The creation of the world is constantly joined in the destruction of the world in mythic narratives” (440). Viewed through a different lens, one where the dismemberment happens willingly, the earth is the gift of the Goddess, and the reciprocal sacrifice that humans offer is their gift to her.

Báez-Jorge sees the Earth Goddess as the center of a quadripartite group of deities: Cóatlicue as the origin of the celestial deities; Chicomecóatl as the provider of sustenance; Cihuacóatl as motherhood and death;and Chalchiuhtlicue as controlling terrestrial waters. In the center is the Earth Mother, the “sacred essence that incorporates the totality of the numinous characteristics that are dialectically linked (human fertility and vegetation; life and death; phases of the moon, etc.) and in turn that which is realized by an internal connection that unifies these distinct responsibilities” (132-133).

The Jaws of Life and Death

Tlaltecuhtli is the earth incarnate, the in-carn-ation of the earth; the earth made flesh. The Earth Goddess embodies the duality of creation and death. The Goddess has her mouth open to give and receive in reciprocal relationship with those who dwell in her.

A song from the Nahua peoples of San Miguel in Sierra del Puebla beautifully portrays this relationship of earth and human. The earth, the most holy earth, is the source of life for the people of San Miguel. As they themselves say here:

We live HERE on this earth (stamping on the mud floor)

We are all fruits of the earth

The earth sustains us

We grow here, on the earth and lower

And when we die, we wither on the earth

We are ALL FRUITS of the earth (stamping on the mud floor).

We eat of the earth

Then the earth eats us. (Broda 107)

Notes

- All translations from the Spanish are mine.

- As the primary means of striking fire, flint was symbolic of the debt humans owed to the deities for sustenance and life. Flint knives were associated with sacrifice and were often personified, adorned with eyes and mouths.

- For a fuller treatment of this stele, see de la Garza 2002.

Bibliography

- Báez-Jorge, F. (1988). Los oficios de las diosas [The offices of the goddesses]. Xalapa, Mexico: Universidad Veracruzana.

- Broda, J. (1987). “Templo Mayor as Ritual Space”. In J. Broda, D. Carrasco, and E. Matos Moctezuma The Great Temple of Tenochtitlan: Center and Periphery in the Aztec World. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 61-123.

- Carrasco, D. (1995) “Cosmic Jaws: We eat the Gods and the Gods Eat Us.” In Journal of the American Academy of Religion. Vol. 63. No. 3, pp. 429-463.

- Coe, M. D. (1997). Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs. New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Garza, M. de la. (1998). El universo sagrado de la serpiente entre los Mayas [The sacred universe of the serpent according to the Mayas]. Mexico City, Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Markman, R. and P. Markman (1992). The Flayed God: The Mesoamerican Mythological Tradition. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco.

- Miller, M. and K. Taube. (1993). An Illustrated Dictionary of The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

- Pasztory, E. (1998). Pre-Columbian Art. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

- Sahagún, B. (1999). Historia general de las cosas de nueva España [General history of things of New Spain] (A. M. Garibay K., Trans.). Mexico City, Mexico: Editorial Porrúa. (Original work published 1829; written in the 16th century)

- Tate, Carolyn. “Writing on the Face of the Moon”. Manifesting Power: Gender and the Interpretation of Power. Ed. Tracy Sweely. New York: Routledge, 1999. 81-102. Challenging Secularization.Aldershot, UK and Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Originally published Lammas 2009 on Matrifocus.com.